The History of Otaku (Wotaku)

by wota

Posted on 2020-03-01

It's important to understand the history of otaku. When researching the word and subculture, one thing becomes clear: the meaning of "otaku" is riddled with ambiguities. Its definition depends on who's defining it. Media and cultural trends have shaped the term's popular perception over time.

To understand otaku, we have to understand where it came from and how it evolved.

An Alternative to Reality

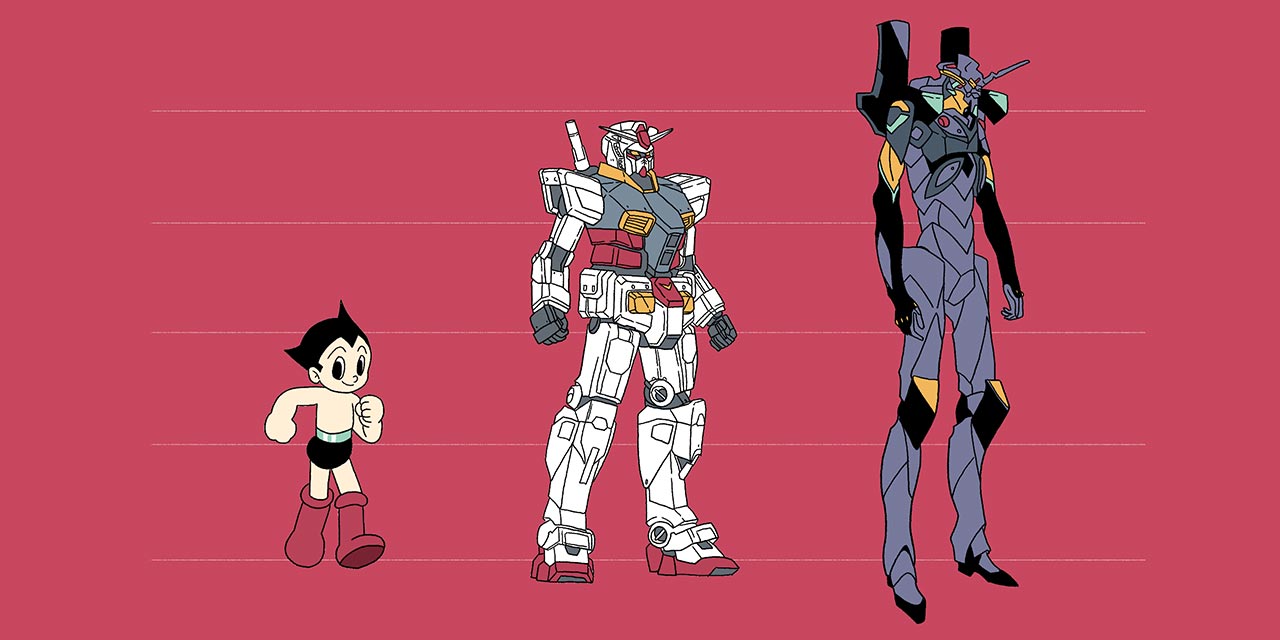

Before the word "otaku," there were people who were interested in manga and anime. Osamu Tezuka's dynamic stories and appealing characters set the wheels in motion. Astro Boy and Princess Knight added deep narratives never seen in manga before. All these and more created passionate fanbases.

During this era, disposable incomes, along with TVs and VCRs, were on the rise. This gave anime a national audience. The new medium became a marketing force throughout the 1980s with Space Battleship Yamato, Mobile Suit Gundam, and other hits.

Disenfranchisement further fueled anime's growth. The youth protests of the 1960s and the economic bubble burst of the late 1980s were harsh realities.

Disenfranchisement further fueled anime's growth. The youth protests of the 1960s and the economic bubble burst of the late 1980s were difficult times. Manga and anime provided a form of escape. The overworked, underpaid, and unemployed found comfort in their fictional worlds.

I couldn't help but relate to this. Weekly episodes of anime I enjoy give me something to look forward to after a hard day's work. One point for "I'm an otaku."

The Origin of the Word "Otaku"

As the manga and anime industries grew, the fandom looked for ways to connect. The 1980s saw a boom in conventions, college clubs, and the overall consumer base. Suddenly there were social events fueled by fictional universes.

Shared interests gave these strangers common ground. But the Japanese language offered no concrete way for unacquainted fans to casually (but not too casually) refer to each other. Famed social critic and anthropologist Eiji Otsuka recalls,

The problem is that in Japan, there isn't a proper word to express you in a situation where you want to speak passionately and personally about something to… someone whose name you don't know, and to whom you haven't been introduced formally. Calling the person by the second-person pronoun anata would sound strange as this is a word used between married couples. There is another second-person pronoun, kimi, but the relationship suggested by the term is too intimate. As a result, fans used the term otaku, which is a sort of honorific, somewhat ambiguous second-person pronoun.

Though the word "otaku" grew semi-organically, one man popularized it within the Japanese nerd crowd. Nakamori Akio, a writer critical of the developing subculture, used the term to describe convention-goers in an article for Manga Burikko magazine in 1983. The rest is history.

オタク(ãŠãŸã)

geek; nerd; enthusiast

The boys were all either skin and bones as if borderline malnourished, or squealing piggies with faces so chubby the arms of their silver-plated eyeglasses were in danger of disappearing into the sides of their brow; all of the girls sported bobbed hair and most were overweight, their tubby, tree-like legs stuffed into long white socks. Now these unassuming classroom corner-dwellers with their perpetually downcast expressions have come out of the woodwork and swelled their ranks into a really rather surprising TEN THOUSAND PEOPLE… For whatever reason, it seems like a single umbrella term that covers these people, or the general phenomenon, hasn't been formally established. So we've decided to designate them as the "otaku," and that's what we'll be calling them from now on.

Although Nakamori's infamous name labeled the fandom, it was contained within the subculture. It took a famous crime to catapult the term "otaku" into the public consciousness. Suddenly, calling myself otaku seemed much less appealing.

The Otaku Murderer

From 1988 to 1989, a man named Tsutomu Miyazaki murdered four young girls in Saitama. His crimes included cannibalism, necrophilia, and vampirism. He even went as far as to preserve body parts as trophies. But despite the bizarre nature of these killings, the media focused on one thing: he had a large collection of anime and manga.

Japanese anthropologist Eiji Otsuka recalls the incident,

News reports on Miyazaki described him not just as a serial killer, but also as an otaku, and this was what really brought the term to the public and shaped perceptions of it. The media implied that Miyazaki committed the crime because he couldn't tell the difference between reality and fiction.

But was Miyazaki a true otaku? Otsuka contends that Miyazaki's media collection lacked the focus required to earn him the otaku name. But others felt his anime filled apartment justified the label. Furthermore, his participation in fanzines and conventions warranted the media's conclusion.

True otaku or not, few sources mention Miyazaki's troubled past, nor the cannibalism, necrophilia, and mutilation that took place. To me, these disturbing details separate Miyazaki from other murder cases and suggest his mental health played a role in the crimes.

Still, the media spun the murder case into a social issue: otaku were the problem. Otaku historian Roland Kelts explains, "The Japanese media branded Miyazaki 'The Otaku Murderer' and people who had never before heard the term 'otaku' came to know its pejorative meaning very well."

The media frenzy surrounding the murders twisted "otaku," giving the term a dark connotation. The murder case became a social issue, and otaku were the problem.

The media frenzy surrounding the murders twisted "otaku," giving the term a dark connotation. This reaction reminds me of the way Western media blamed the 1999 Columbine High School massacre on video games and industrial music, painting the "goth" subculture as sinister.

Even as the fervor over the Miyazaki case died down, otaku's negative stigma remained. To the general public, the group came to represent men who preferred an imaginary world over reality and had trouble differentiating between the two. These fanatics abandoned marriage, family, and health to invest themselves in a "valueless" hobby.

There are more to learn! (Learn More on TOFUGU)

2

Wotaku exchange

オタク, ヲタク

otaku, wotaku exchange

- geek

- nerd

- enthusiast

- expert